Unmasking Shakespeare’s Tragically Evil Queens, Part II: Marriage, Motherhood, and Manipulation

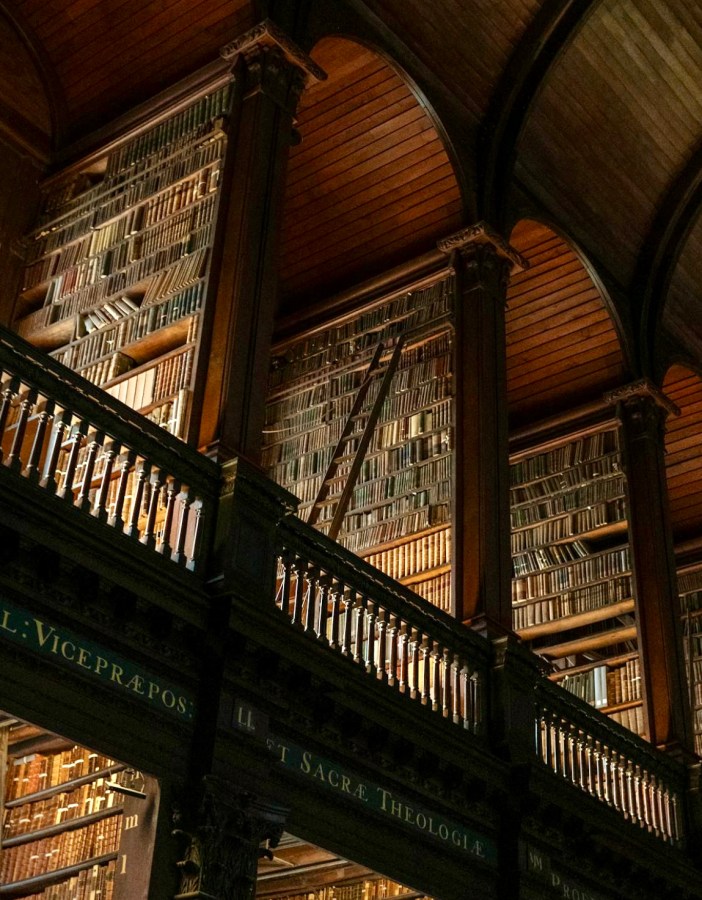

Greetings, wandering soul! The Ink-stained Archivist invites you into the Library of the Lost—where, for each lost soul, a story might be found.

Shall we continue with our feminist analysis of Lady Macbeth’s and Tamora’s descents into immorality?

Power, Privilege, and Peril

Often, the only opportunities for social mobility within the patriarchal societies in which Tamora and Lady Macbeth exist are those that directly correlate to their villainous arcs. Introduced as members of nobility, these Shakespearean women occupy—or, in the unfortunate case of the enslaved Gothic queen Tamora, formerly occupied—roles that most of their female contemporaries would covet. Still, Lady Macbeth, wife to the celebrated Thane of Glamis, upon receiving a letter from her husband recounting a since-confirmed prophecy regarding his unexpected rise to Lord of Cawdor, settles her ambitions upon a much loftier role within Scottish noble society: the throne (Mac. 1.5.5–31). The subsequent calamitous machinations of Lady Macbeth and her husband, concocted to achieve their mutual ambition of fulfilling the witches’ prophecy foretelling their ascension to the Scottish throne, result in multiple murders, broken alliances, a suicide, and a war-torn country thrown into disarray by a tyrannical monarch—all in one woman’s pursuit of social status. On the other hand, Tamora knows all too well the cruelties wrought by war, especially those committed against society’s women. Captured in the aftermath of defeat, this proud former queen of the Goths and her three once-royal sons are enslaved by the titular Titus Andronicus, a famed General of enemy Rome (Tit. 1.1), thereby revoking her royal status. Shakespeare’s reimagining of ancient Rome, as depicted in Titus Andronicus, is strictly patriarchal and male-dominated (Willis 22), its women relegated to supportive roles with little influence. As an enslaved woman—a rank of subservience—Tamora is powerless to intervene when her eldest son, Alarbus, is sacrificed to appease the ghosts of Titus’ twenty-one sons, who perished in battle (Tit. 1.1). When the role of wife and Empress to the Roman Emperor Saturninus is offered to her, Tamora accepts, recognizing this social ascension as an opportunity to reclaim her lost power and pursue revenge against Titus for the death of her son (Tit. 1.1). As illustrated, the dynamic social evolutions and shifts in societal power that define Tamora and Lady Macbeth propel these notorious villainess toward their inevitable downward arcs.

Marriage, Manipulation, and Machinations

Unfortunately, a woman’s access to power under such patriarchal societies is typically dependent upon her proximity to powerful men. Through their marriages to influential men, Tamora and Lady Macbeth are granted what little power is permitted to women of circumstance. Unsatisfied with this arrangement, both women, like countless others within Shakespeare’s myriad works, participate in “a long-standing tradition of women who seek to gain power both through and over their husbands” (Martin 22) as a means of indirectly exerting social influence within a male-dominated political structure (Martin 11). Because she is unable to seize the Scottish throne for herself, Lady Macbeth manipulates her weak-willed, yet still ambitious husband into securing it for them both (Snodgrass). Where Macbeth promises his wife societal power in his attainment of the Scottish crown, the Emperor Saturninus provides his new wife with the security granted to the consort of Rome’s most powerful man. In reference to her recent abrupt social ascension, Aaron the Moor, Tamora’s paramour and ally, proclaims the Empress “safe out of fortune’s shot” (Tit. 2.1.2). All power granted to Tamora as Rome’s new Empress is dependent upon, and reinforced by, the political power bestowed upon Saturninus as the Emperor of Rome.

Masculine Masks and Monarchic Motivations

This dependence upon men forces Lady Macbeth and Tamora to exploit their patriarchal societies’ traditionalist ideals of gender and manipulate their husbands into aligning their desires with those of their wives. Even women in relatively powerful positions, like the noble Lady Macbeth and Tamora as the Empress of Rome, must still navigate around and through the wills of their male counterparts—an accepted rite of passage for Shakespeare’s women (Martin 3). Throughout the early acts of the play, Lady Macbeth uses her husband’s insecurity against him, wounding his fragile masculinity and tempting his latent ambitions, thus assimilating his weaker will to better serve her own more dominant, apparently masculine-minded convictions. Lady Macbeth bullies and goads her husband, the Thane of Cawdor and Glamis, into murdering his liege, the Scottish king, to fulfill her own ambition of power through her husband’s ascension as monarch. Later, when, in a moment of anxiety and guilt, Macbeth fails to adequately complete the sinister tasks his wife judges necessary, Lady Macbeth wrests command of the pair’s violent scheme and frames the king’s servants for his murder, all while she continues to contemptuously insult her beleaguered husband’s waning masculine pride (Mac. 2.2). Only after this continued assault on his masculinity does Macbeth begin to independently embody those traits which his wife favors in a companion and co-conspirator. Her frequent aggressive attacks of Macbeth’s manhood “challenge his warrior’s identity” (Sharif Talukder 1671) as asserted to the audience via his feats of valor in combat against Scotland’s enemies (Mac. 1.3). This ultimately drives him to emulate Lady Macbeth’s societally-idealized masculine persona in order to earn her respect and admiration. In moments of unmasculine weakness, when Macbeth’s guilt and fear drown his thirst for monarchical power, Lady Macbeth deftly provokes her husband’s manhood. Her pointed utterance of “When you durst do it, then you were a man” (Mac. 1.7.49–51) feeds the flagging flame of Macbeth’s masculine ego, ultimately leading to the gruesome murder of his liege and friend, the king of Scotland.

Dominance and Deception

Tamora, too, manipulates her husband Saturninus, and through him his imperial influence, to further her quest for revenge. At various points throughout the play, Tamora can be seen whispering to her imperial husband, offering promises of retribution against their shared enemy, the Andronici. From the inception of their relationship, Tamora establishes a habit of wielding her feminine charm to convince her new husband to value her counsel above his own opinions. Donning the guise of peace-weaver, the loss of her eldest son still fresh in her mind, Tamora entreats her “sweet Emperor” to forgive the Andronici their transgressions against them in favor of unity in Rome (Tit. 1.1.450–476). In a tone not intended to carry past her new husband’s ears, however, Tamora weaves words of chaos and destruction, vowing to serve as Saturninus’ dutiful ally as they seek their revenge, which further draws him into her thrall. Similar moments of secretive, sinister communion between the imperial couple abound in the successive acts, culminating in the attainment of their coveted revenge, followed swiftly by their violent demises, arranged for them by Titus, who recognized in both Saturninus and Tamora an adversary whose combined efforts destroyed the noble Andronici. In warning his enraged brother to reconsider his hasty oath of vengeance against the sons of the Emperor’s wife for their assault of Lavinia, Titus acknowledges the effectiveness of the she-bear Tamora’s feminine sexuality as a method of manipulating “the lion” (Tit. 4.1.102) Saturninus to accede to her dastardly desires. Tamora’s manipulation of Saturninus depends on their shared thirst for revenge, as well as her continued value as an ideal wife, mother of his heirs, and sexually desirable partner.

Motherhood, Madness, and Murder

Tamora’s dedication to her societally reinforced role as the devoted mother of three Gothic princes acts as the catalyst to her vengeance-motivated villainous deeds, just as Lady Macbeth’s callous refusal of society’s demand that she prioritize traditional womanly duties over her own desires is infamous evidence of her ruthless willingness to trade maternity for power. In many respects these notorious literary villainesses stand as antitheses of the other. This is most apparent in their relationship with the gendered task of motherhood. With the memory of “A mother’s tears” shed while pleading for Titus Andronicus to spare her eldest son’s life (Tit. 1.1.103) still fresh within her mind, Tamora seeks to secure her remaining sons’ safety and happiness in foreign Rome. To Alarbus’ grieving Gothic mother, his ritual sacrifice at the hands of Roman Andronici was a barbarous, cruel act of murder (Willis 35) and further confirms Tamora’s maternal responsibility for her remaining sons. Demetrius, one of Tamora’s two remaining sons, urges his grieving mother to remain hopeful, reminding her that divine forces might grant her an opportunity to enact vengeance (Tit. 1.1.135–41). His continued encouragement comforts his mourning mother as she pursues revenge against Titus and the Andronici, whom she blames for her eldest son’s murder. After the newfound security afforded to Tamora and her sons by their tenuous status as members of the imperial household is threatened by Lavinia and Bassianus, who plan to defame the Empress’ reputation to the Emperor Saturninus after witnessing a romantic rendezvous between Aaron and his Empress (Tit. 2.3.65–86), Tamora’s response is immediate and impassioned. “Your mother’s hand shall right your mother’s wrong,” (Tit. 2.3.125) she proclaims, delivering an acknowledgement of her duty as a mother to protect her sons from perceived harm. In contrast, Lady Macbeth’s disregard for the feminine-aligned role of nurturing mother is at odds with Tamora’s maternal determination to protect and guide her sons. In ferociously demanding of the arcane forces that govern the mortal world to “unsex” her and replace her nourishing, life-affirming mother’s milk with bitter, masculine gall so that she may pursue her darkest, deadliest desires without the feminine burden of remorse (Mac. 1.5.45–53) Lady Macbeth denounces the motherhood expected of her by a patriarchal society in favor of embodying her definition of masculine cruelty (Kimbrough 182).

Maternal Maleficence

As such, infanticide, arguably one of the greatest acts of evil a mother might commit against her own vulnerable offspring, is relevant to the downward character arcs of Lady Macbeth and Tamora. Imaginary or literal, both Tamora and Lady Macbeth exhibit a willingness to end the life of their own children in order to safeguard their interests. When Tamora’s labor pains begin, the Roman imperial household is ecstatic, eagerly awaiting the birth of Emperor Saturninus’ heir. Excitement quickly turns sour however, when the Empress is delivered of a son who undeniably resembles her affair partner, Aaron the Moor. To preserve her and her sons’ status within Rome, Tamora coldly orders Aaron to murder their newborn son, the irrefutable evidence of her unfaithfulness (Tit. 4.2.81–85). Though childless during the events of her play, Lady Macbeth’s sinister promise to her husband, to pluck her nipple from their defenseless infant’s hungry mouth and bash in its skull out of loyalty to their bond and shared goal of power (Mac. 1.7.61–64) further emphasizes her unwillingness to relinquish her masculine-aligned ambitions of power to perform the feminine burden of nurturing a son who might one day instead possess the power she covets (Snodgrass). This odious image of an apathetic mother who is willing to murder her own infant divorces Lady Macbeth from a woman’s socially ascribed occupation of motherhood (Martin 21). Lady Macbeth’s fierce willingness to brutally murder her imaginary infant mirrors Tamora’s callous call for the death of her literal illegitimate son. These women, declared villains by audiences for their involvement in crimes unrelated to the above circumstances, nonetheless express an abominable readiness to kill their offspring, which is contrary to the nurturing, maternal nature attributed by society to women.

Feminine Facades and Masculine Masks

The villainous arcs of Shakespeare’s Tamora and Lady Macbeth are informed by their diverse experiences as women in their fictional patriarchal societies. Morally gray characters abound in Shakespeare’s works, as villains and heroes alike perpetuate cycles of violence and cruelty in the name of their goals. Few in Shakespeare’s tragic tales are free of sin or unsullied by blood, and all are burdened by the constraints of patriarchal dogma. It is the women—and, for the purposes of this argument, Tamora, former Queen of the Goths, Empress of Rome and Lady Macbeth, the mad queen of Scotland’s deposed tyrant king—whose admittedly reprehensible actions are most worthy of a balanced analysis. Tamora’s crimes were pursued in response to horrifying circumstances committed against her family by powerful Roman men. Her fictional female contemporaries, who possess little power and autonomy, are forced to rely on the grace of men to accomplish their goals and secure their safety. Lady Macbeth, despite her influence as a noble Lady and wife to a trusted thane, desired more for herself than what she might acquire indirectly from a husband or son. Her allegedly unwomanly ambitions and determination to obtain ultimate monarchical control in Scotland via murder and manipulation are acts weighed almost as equally reprehensible as her denouncement of her societally-assigned feminine duties. Lady Macbeth and Tamora pursue such malicious deeds because the men in power who surrounded them and the male-dominated society in which they each languished since birth led them to believe there were no moral or respectable methods available to women.

Ah, but I’ve paddled on enough, haven’t I? As you might have noticed, I care very deeply about this topic. Depictions of women in works of fiction—especislly those of controversial or complex women—enthrall me.

If you’ve enjoyed this moment of literary mischief, please consider subscribing to Myths and Mischief. Each time we publish a new article, an enigmatic, technologically-skilled wizard will promptly notify you. But please, I beg you not to make me explain how any of that nonsense is accomplished; I would hardly know where to begin, I’m afraid.

Your Ink-stained Archivist bids you farewell.

Works Cited

Biswas, Prarthita, et al. “Portrayal Of Gender Dynamics In Shakespeare’s Macbeth.” Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results, vol 14, no. 2, 2023, pp. 2706-2711, DOI: 10.47750/pnr.2023.14.S02.317.

Kimbrough, Robert. “Macbeth: The Prisoner of Gender.” Shakespeare Studies, vol. 16, Rosemont Publishing and Printing, Jan 1, 1983, pp. 176-190. EBSCO.

Martin, Aubrey. Bad Women and “a Spirit to Resist”: The Archetypes of Female Villainy in Shakespearean Drama. Apr 5, 2024. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Honors Thesis. DOI: 10.17615/sfxe-r658.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. HarperPerennial Classics, Dec 16, 2014.

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. HarperPerennial Classics, Dec 16, 2014.

Sharif Talukder, Ahmed. “The Dominance Of Lady Macbeth On Macbeth’s Collapse In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, A Discussion.” Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, vol. 35, no. 1, Aug 10, 2023, pp. 1668-1676. DOI: 10.59670/jns.v35i.3830.

Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. “Lady Macbeth and Feminist Literature.” Encyclopedia of Feminist Literature, 2nd ed., Facts On File, 2013. Bloom’s Literature, online.infobase.com/Auth/Index?aid=99121&itemid=WE54&articleId=42763.

Willis, Deborah. “‘The gnawing vulture’: Revenge, Trauma Theory, and Titus Andronicus.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 53, no. 1, Oxford UP, Apr 1, 2002, pp. 21-52. JSTOR, DOI: 10.1353/shq.2002.0017.

Discover more from BASIC Studios

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply